Paul ThekPaintings, Works on Paper, and Notebooks 1970–1988

Past exhibition

Paul Thek Paintings, Works on Paper, and Notebooks 1970–1988

About the Exhibition

The Arts Club of Chicago is pleased to announce the first one-person exhibition of the American artist Paul Thek (1933–1988). Paul Thek: Paintings, Works on Paper and Notebooks 1970–1988 features over eighty examples of work from the last two decades of his life, and will open on Thursday, December 3 and run through January 23, 1999.

Thek was a spiritual man whose early religious experiences permeated his life and work. He was an artist who always worked outside the mainstream, commenting on the brutality of our technologically mechanized, spiritually devoid modern world. Because he decided to spend a large part of his career in Europe, his work was virtually unknown in the United States. Thek’s artwork took many forms: sculpture, painting, watercolor and installations. His major installations were ephemeral, with only photographs left to document their existence. From the vast quantity of work produced, what remain are the sculptures, paintings, works on paper and notebooks which offer great insight into the mind of the artist.

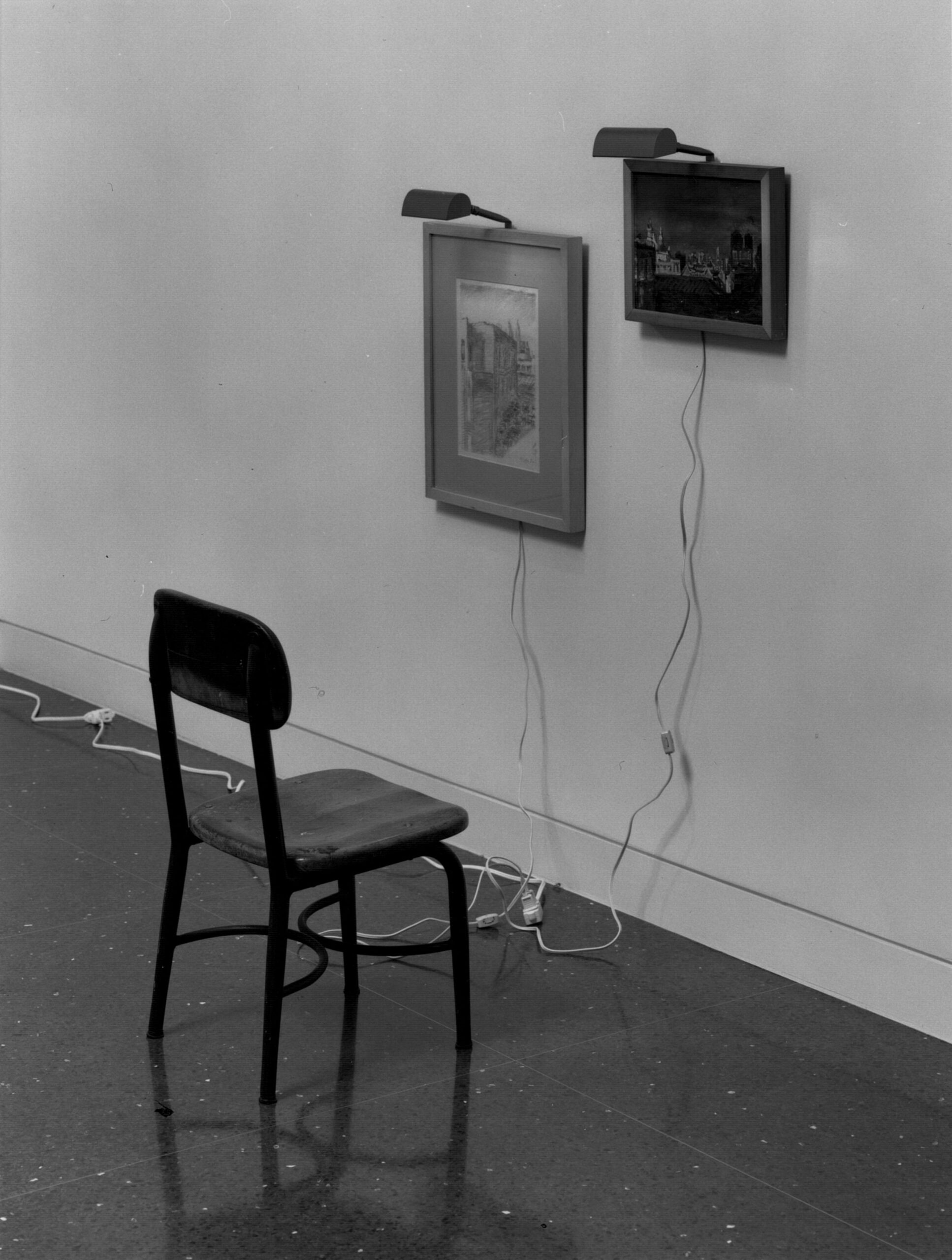

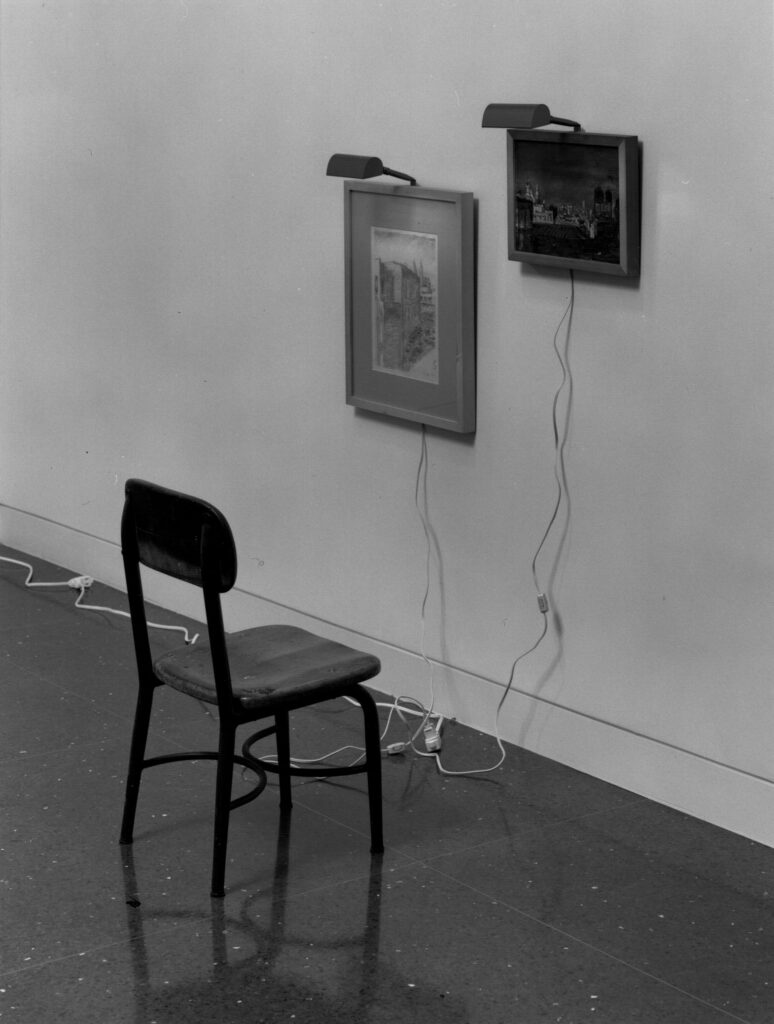

The Arts Club exhibition recreates the “swimming pool” installation, which Thek first installed at the Mokotoff Gallery, New York in 1987. The aqua-blue-green small paintings and works on paper are installed two feet off the ground, surrounding the viewer in a pool of color evoking water. Many of the pieces contain written comments—either derogatory, comical or spiritually inspired—such as the heraldic ribbons proclaiming “compassion” or “diligence,” or a phrase painted amid the water-like brush strokes reading “the soul is the need for the spirit”, or the three part pun, “ecole de fish.” Thek’s “picture light paintings” are presented in cheap gold-leaf frames with overhanging lights illuminating “bad” paintings which annotate the many styles and movements of the 70s. Both bodies of work comment on the museum community; they stretch the boundaries of what is considered “good” art and inquire about standard museum installation practices. They also illustrate Thek’s lifelong conundrum: he desperately sought recognition from the museum community that his work often derided.

Also on exhibition is a sampling of Thek’s notebooks which he began keeping in 1970 and continued until the end of his life. These notebooks are a rich record of the inner workings of his mind and his sources of inspiration. Over the course of eighteen years he filled over a hundred books. They are a jumble of his personal recollections, comments on his environment, transcribed texts, sketches, doodles, complete drawings and watercolors. They are random and disorganized, silly, personal, witty, or dark depending to which page you turn.

About the Artist

He began using newspaper in the late 1960s; it became a signature medium reinforcing his sense of time passing. He painted over the newspaper with acrylic or oil, creating a ground for sketches of subjects as potatoes, dinosaurs, the earth and the sea, and themes that changed as his interests changed. In this work, Thek’s sense of whimsy, curiosity, humor and spiritually is captured.

Although his work chronicled and mirrored the events that spanned his career, late 1950s to 1988, he did not attain the recognition of such contemporaries as Andy Warhol, Donald Judd or Roy Litchenstein. His Technological Reliquaries or “meat pieces,” are possibly his best known work. Made in reaction to the Pop and Minimal movements, they were his attempt to humanize the slickness of the art produced by his fellow New York artists. These sculptures are composed of wax, paint and hair simulating torn flesh, hunks of meat and disembodied limbs. He encased the manufactured meat in sleek Plexiglas cases, liking the way the dissimilarity of the materials played off each other.

The Technological Reliquaries series culminated in his first installation, The Tomb—Death of a Hippie which was shown at Stable Gallery and at the Whitney Museum in 1967. Lying inside a pyramid-shaped tomb was a pink wax cast of his body, clothed in pink, his tongue protruding, and the fingers of his right hand cut-off and placed in a bag above his head. This piece encapsulated his feeling of the death of the hippie/artist, a loss of power and isolation, encased in an anti-minimalist statement. The Tomb is one of Thek’s most recognized pieces but, as with most of his installation work, was dismantled and destroyed over the course of his lifetime.

In the end of 1967, he moved to Europe where he spent most of the next decade. His work reflected this change and he moved away from object-centered work to installations. He also began working collaboratively with other artists. In this comfortable environment, his strong sense of spirituality came to the forefront. Raised a Roman Catholic and steeped in the rituals of the church, he sought to recreate the mystery, aura and spiritual nature of his experience. Many of his installations were timed to coincide with Roman Catholic feast days, such as Easter and Christmas. In his Processions series he compiled found objects such as boats, stuffed stags, rabbits and deer, gnomes, newspaper and sand towers creating installations that recalled the spirit of church ceremonies.

In the 90s, Paul Thek’s essence can be found in the work of the artists Robert Gober, Mike Kelley, Kiki Smith and Charles Ray. The human body is once again under examination, making Thek’s Technological Reliquaries as relevant today as they were in the 60s and installation has once more become a predominate method of presentation. In our technically saturated, mechanized world the search for the spiritual continues.